ADVERTISEMENT

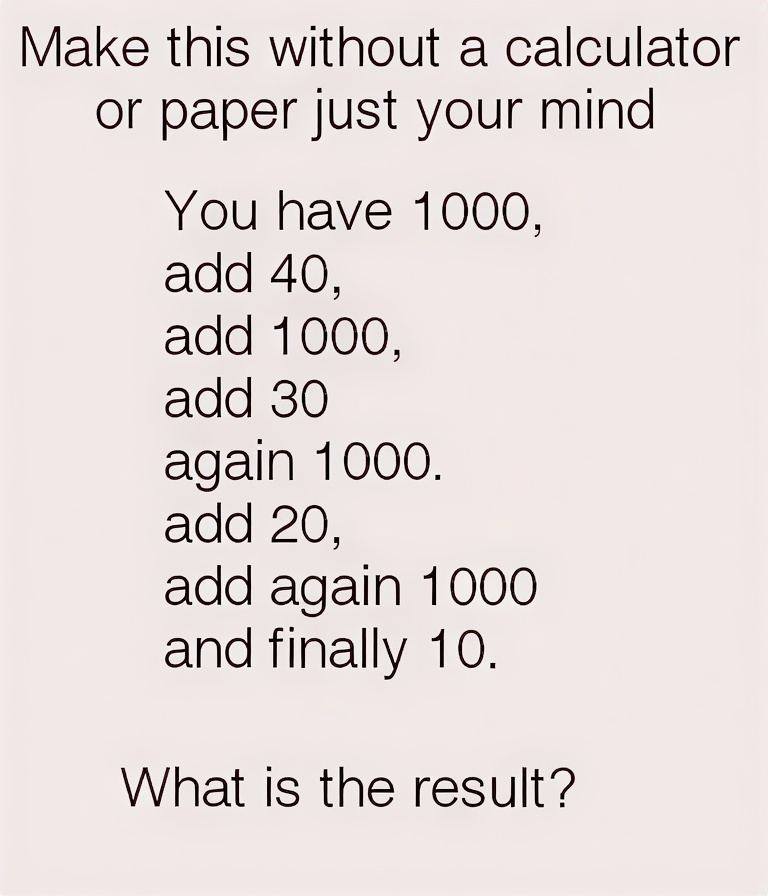

Your Math Skills: The Simple Problem That Keeps Stumping People”

A Slow-Simmered Stew for Learning Why Rushing Gets Us the Wrong Answer

The Question That Looks Easy

“Test your math skills.”

Four words that sound harmless. Almost playful.

Then comes the problem.

It’s short. Clean. Elementary-school simple. The kind of equation that makes people confident enough to answer without checking their work.

And yet… people keep getting it wrong.

Not because they can’t do math — but because they rush.

This recipe is about that exact mistake.

It’s a slow-simmered stew, the kind that punishes impatience and rewards attention. The kind of dish that looks forgiving but absolutely isn’t if you don’t respect the process.

Just like simple math.

Why a Stew?

Because stew teaches the same lesson that tricky “easy” math problems do:

Ingredients matter, but order matters more

Heat must be controlled

Time cannot be skipped

Confidence without care leads to failure

You can’t eyeball it.

You can’t rush it.

And you definitely can’t multitask through it.

Ingredients (Serves 6, plus leftovers that taste better after reflection)

The Base

900 g (2 lb) beef chuck or lamb shoulder, cut into large cubes

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

2 tablespoons olive oil

The Logic Layer

2 large onions, diced

4 cloves garlic, minced

2 tablespoons tomato paste

The Structure

3 carrots, sliced thick

3 potatoes, cubed

2 celery stalks, chopped

The Variables

1 teaspoon paprika

½ teaspoon cumin

1 bay leaf

Fresh thyme

The Equation

1 liter (4 cups) beef broth

1 cup water or red wine

Step 1: Read the Problem Carefully

Before you turn on the stove, read the recipe all the way through.

Most people don’t.

That’s mistake number one — in math and in cooking.

Season the meat generously with salt and pepper.

Heat olive oil in a heavy pot over medium-high heat.

Brown the meat in batches.

Not all at once.

Crowding the pan lowers the temperature, just like rushing through a problem lowers accuracy.

Step 2: The False Confidence Phase

Remove the meat and set it aside.

Lower the heat slightly.

Add onions to the same pot.

They’ll soak up the browned bits — the hidden information people overlook when they jump to conclusions.

Cook slowly until translucent.

Add garlic.

Then tomato paste.

Stir and let it darken slightly.

This step looks optional.

It isn’t.

Skipping it is like ignoring order of operations.

Step 3: Assemble the Equation

Return the meat to the pot.

Add carrots, potatoes, celery.

Sprinkle in spices.

Add bay leaf and thyme.

Now pour in broth and water (or wine).

Everything is submerged, balanced, accounted for.

At this moment, the stew looks finished.

Just like the math problem looks solved.

But it’s not.

Step 4: The Part Everyone Tries to Skip

Bring to a gentle boil.

Then reduce heat to low.

Cover partially.

Simmer for 2½ to 3 hours.

This is where impatience ruins everything.

People lift the lid too often.

They crank the heat.

They assume more intensity means faster results.

It doesn’t.

It just makes the meat tough and the sauce thin.

What This Teaches (Without Saying It Out Loud)

That viral math problem doesn’t fool people because it’s hard.

It fools them because:

It looks familiar

It feels easy

It rewards overconfidence